Flying Inside the Hurricane

Strategy Tools for the Historic Inflection Point We're Experiencing

By Marc E. Babej and Stephen Bungay

Today’s business environment is not for the faint of heart: Change, driven by promising but also disruptive technologies, is fast paced as never before. While disruptors have been rife, so too Black Swans have been coming in flocks: Recent weeks have seen the largest disruption to global trade in at least a century, including the 2024 EU–US Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, U.S.–China tech export bans and 125% tariffs that make the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act look tame. This is on top of an environment that had already witnessed the first major global pandemic in a century, ensuing supply chain disruptions not seen since the 1970s and the highest inflation rates since the early 1980s. In many Western nations, political and societal polarization have risen to levels not seen since the 1930s. Globally, we are witnessing increasingly severe impacts of climate change, arguably the biggest war since World War II (Russia-Ukraine) and the specter of escalating geostrategic tensions between the US and China.

The double helix of discontinuity

We are living through a historic inflection point beyond living memory: a double helix of accelerated, disruptive change on the one hand, and elevated uncertainty on the other. This is spelling trouble for businesses that fail to adapt their strategy processes and tools to a new reality – one in which long-term planning is tricky and structural competitive advantages are less sustainable. However, for businesses able to adapt, discontinuity may present epochal opportunities.

The first strand of the discontinuity double helix is accelerated, often disruptive, change—largely driven by new technologies. What used to take a decade may now happen within a year; what used to take a quarter may now happen in a month. Production cycles have sped up, it’s harder than ever to maintain a lasting competitive advantage and customers have unprecedented information power at their fingertips. Case in point: The accelerating impact of generative AI is calling into question key assumptions about employment, productivity, organizational behavior and customer relationships.

What began as a crowded field of foundational models—led by OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, Google’s Bard (now Gemini), and Meta’s LLaMA—has exploded into a full-spectrum AI arms race. These aren’t just tools, but platforms reshaping entire industries—from search and productivity to creative work and software development. Microsoft’s integration of OpenAI’s models across its ecosystem via Copilot has set a new benchmark for enterprise software, while Claude 3 Opus and GPT-4.5 have raised the ceiling on reasoning, memory, and complex task execution. Meta’s open-source models are increasingly embedded across the developer economy, and Perplexity is challenging incumbents in real-time search. Yet the biggest strategic shock came in early 2025, when China’s DeepSeek-V2 matched—and in some benchmarks, surpassed—the performance of its Western peers using a radically more compute-efficient architecture. It was a Sputnik moment, a vivid reminder that the future of AI will be shaped not only by innovation, but by global competition.

The second strand of the discontinuity double helix is elevated uncertainty: volatility at macro level, manifesting in the global economy, politics, social tensions, public health and geopolitics – that intrude on business relationships and operations. Generations of executives in developed economies had the luxury of a generally stable macro environment throughout their careers. Today’s elevated uncertainty is unfamiliar terrain.

Risk is not the same as uncertainty

Some may argue that a senior executive worth their salt is used to managing risk. “Risk” and “uncertainty” are often used interchangeably — but in fact, they are very different beasts. Risks are possibilities within a static context: the rules of the game are stable and known; accordingly, they can be quantified based on precedent. A chess player takes risks: she can assess the potential opportunities and threats of each move based on precedent data, which she knows to be relevant because the rules of the game have been largely static for centuries. Even in a game of chance, the odds can be assessed, because the context, though high-risk, is static.

“Risk assumes a rulebook. Uncertainty reminds us there might not be one.”

However, strategy crafting — also during calmer times — is not analogous even to a game of chance, because the context is dynamic: there is no all-encompassing rule book, and patterns can change without much advance warning. Further, even if a business decisionmaker is aware that the rules pertaining to a decision have changed, it may not yet be clear how they have changed (Donald Rumsfeld’s “known unknowns”). Therefore, decisionmakers today cannot assume past data is relevant to decisionmaking about the future. What makes today’s uncertainty radical is that, as Rumsfeld put it, “there are unknown unknowns” — uncertainties that are so outside the realm of the imaginable that they escape advance consideration.1

In periods of radical uncertainty, both known unknowns and unknown unknowns factor so significantly that they must be considered a definitional aspect of decisionmaking and strategy crafting. As the philosopher Karl Popper framed it: “Our knowledge can only be finite, while our ignorance must necessarily be infinite.”

Many of the traditional strategy tools, such as Porter’s five forces and value chain, speak to timeless truths about analyzing businesses in relation to industry competitors. However, these tools were devised decades ago, for a slower-paced and more stable macro environment.

The traditional toolkit alone can’t properly address the challenges posed by discontinuity — but there are tools that can help companies function, even thrive, in such an environment.

The new strategy toolkit

Tools for strategy-crafting in discontinuity

The accelerated pace of change in times of discontinuity calls for faster situation assessment and decisionmaking and response. As Charles Conn and Rob McLean showed so convincingly in In Uncertain Times, Embrace Imperfectionism, the best information and insights available now, even if imperfect, may well be preferable to the perfect set of data available a month from now.

Those who have better tools for intelligence collection and analysis can shift the odds in their favor. The key is to pick up weak signals early and often, distinguish them from background noise, identify their implications and draw the right conclusions —ahead of the competition.

1. A market radar, not a snapshot

A market radar is to traditional competitive studies what an intelligence report is to an academic treatise: it supports agile decisionmaking and thereby enables shorter reaction times by identifying, tracking, and analyzing changes in market, competitive and exogenous dynamics at short intervals. Intelligence must be conducted continuously, and reports should be distributed to executive leadership and relevant functional leaders quarterly, for particularly fast-paced industries even monthly.

2. The analysis dipstick

Managing today calls not for lengthy progress reports, but what we call an analysis dipstick, which determines a finite set of critical metrics delivered at short intervals. Traditional progress reviews are held at set intervals and focus on ‘how we are doing’ relative to the plan. They often employ a ‘traffic light’ system. The discussion typically homes in on the red lights and the question is how to ‘get back on track’.

This focuses the discussion on the past, and makes the dubious assumption that the original plan was right. But when uncertainty is the new “normal”, change must be the operating assumption, and success is a function of continuous learning as events unfold. The real question is “what is the situation now?” and therefore “what actions are we going to take going forward?”

“The point of strategy isn’t to stay on track—it’s to stay in command when the track disappears.”

3. Operating rhythm as organizational heartbeat

The way to do this is to establish an operating rhythm, which reflects the heartbeat of the organization, and may be fast or slow. The speed of the beat depends on the rate of change in the environment and the speed of response needed to make changes. Retailing, for example, may need to respond in days, R&D in months.

More important still is how you begin each meeting. Rather than asking “are we on track?”, ask “how has the situation changed?” The analysis dipstick should be designed to identify environmental changes and to track the effects your current actions are achieving. If the answer is “no – the situation has not changed”, you can then move on to look at the numbers. If the answer is “yes, it has”, the next question is “so what do we now need to do differently?”

4. Living documents, not dead decks

In a fast-moving environment, a concise, actionable plan on an etch-a-sketch is preferable to a plan that is “chiseled in stone” but approaches obsolescence by the time it is presented. PowerPoint presentations and long-form text documents – still the standard in many organizations – harken back to yesteryear’s less frantic business environment. Nowadays, to pursue “perfectly comprehensive” is to risk falling behind the curve.

The tools we use not only represent our thinking, but also shape how we think: presentations and long-form text documents have a linear structure that makes them ill-suited to adaptation. Rather, discontinuity calls for “living documents” with a modular structure that is intended for continuous adaptation.

Mind maps are at the core of strategy crafting in our practices, because they invite users to approach strategy as dynamic. The radial format shows the whole and its component parts at the same time, enabling both linear and lateral thinking. This. In turn, invites experimentation, to reflect shifts in circumstances and integration of new insights.

Discontinuity is, by definition, a bumpy ride. Accordingly, strategies themselves must be “ruggedized,” by considering a wider range of possible circumstances. Tools must be suited to accommodating this increased optionality. To deliver optionality, strategy tools need to be different in nature. High uncertainty places a significant premium on assessing a range of possible near-futures. What’s needed now are tools that integrate real-time information, to game out a range of contingencies.

“What used to take a decade now happens in a year. What used to take a quarter happens in a month.”

Tools for radical uncertainty

Notwithstanding the fundamental differences between head-on contests, such as warfare, and preference contests, such as competitive business strategy, some of the new tools we use derive from the school of strategy with the most extensive track record – military strategy, because it was designed with a rapidly changing and highly uncertain environment in mind. Military conflict, which gave birth to the concept and practice of strategy about 2,500 years ago, has long been an environment of radical uncertainty. Successful commanders recognized conflict to be fundamentally dynamic and placed great emphasis on ‘human factors’. Not by coincidence, the level of military strategy most analogous to business strategy, is termed operational art. These tools are dynamic (showing movement and change, also over time) and, crucially, scenario-playable.

6. Market maps: seeing terrain, not just targets

In our practice, we have developed a market mapping tool (fig. 1), which visualizes key aspects of the strategic environment, such as competitive saturation and concentration/fragmentation of a market, key audience demographics and needs and flows to/from relevant product categories. By using geographic features as a metaphor (rivers as obstacles, mountains as opportunities, etc.) it allows users to quickly identify and gauge market situation and opportunities.

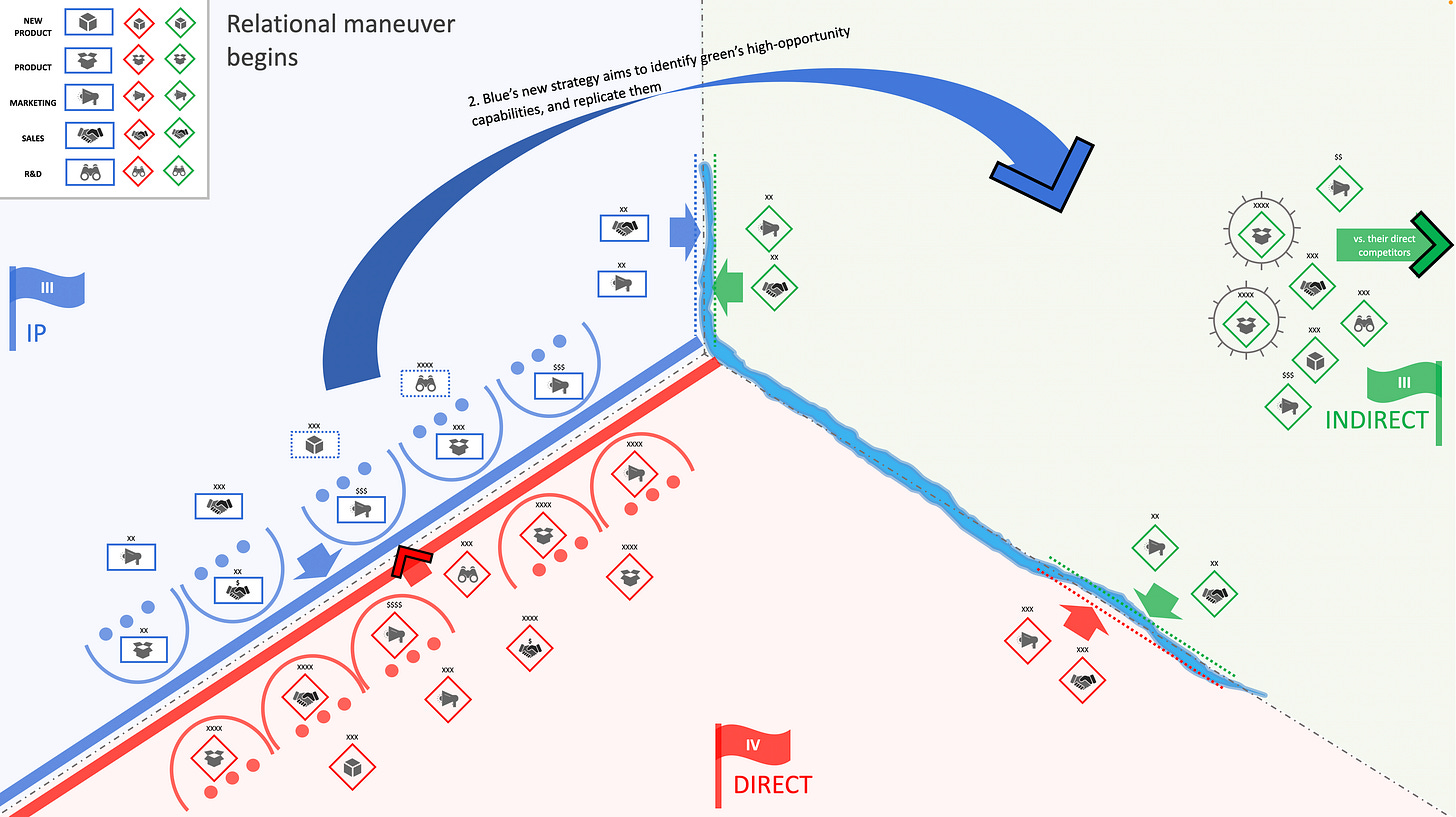

7. Strategy mapping as strategic rehearsal

In conjunction with market mapping, we have also developed a competitive strategy mapping tool (fig. 2), which enables companies to literally see a strategy playing out vis a vis the competition. It overlays assets in key functional disciplines (product management, product development, marketing, sales, R&D) onto key metrics such as market share, and considers competitive strength, marketplace and competitive obstacles. Making strategy visible in this fashion facilitates explaining strategic rationale – and, crucially, uptake across disciplines and levels within the organization.

Scenario planning isn’t entirely new to competitive business strategy, but hasn’t been a standard feature of strategy development processes. Unlike militaries, where map-based scenario planning exercises are foundational to strategy development and execution, scenario planning in business has tended to fall short of its promise: “Our Excel sheet, or bullets on white board, vs. your or Excel sheet, or bullets on a white board” falls short of the multivariate considerations required for effective scenario planning exercises. Competitive strategy mapping applies the symbology of military mapping – and, just like military maps, is optimized for gaming out scenarios in real-time “red team” planning exercises.

8. Strategy briefings for alignment and intent

To create a ‘strategic plan’ in a discontinuous environment is to invite irrelevance. Militaries do a lot of planning, but it is designed to prepare them for a set of multiple futures. The need to set direction and align around current decisions – while always being prepared to adapt “when the facts change.” They do this by replacing the ‘plan’ with an intent, which expresses what the organization is seeking to achieve and why. It is a concise expression of the desired high-level outcome. To turn that into action, they use a tool they call ‘mission analysis’ and we call strategy briefing.

Starting with a high-level statement of intent crafted by the CEO or senior team, direct reports work out what the implications are for their area of responsibility. That involves answering five apparently simple questions:

What is the context? (including factors specific to their area)

What is the higher intent one and two levels up? (i.e. what is the intent of my boss and my boss’s boss)

What is our intent? (what do we in our specific area have to achieve to contribute to the achievement of the overall intent?)

What are the implied tasks? (what are the responsibilities of the people on the next level down in contributing to achieving my intent?)

What are the boundary conditions we must observe (expressed as freedoms within the boundary, and constraints which define the limits of our freedom of action)

Producing a good briefing is surprisingly demanding. It forces executives to think hard about the fundamentals of their business. Most executives spend most of their time worrying about operations. Operations matter, but you also have to do the right things in the first place — and to continually question whether the ‘right thing to do’ has changed.

The traditional strategy tools have served us well for many years and will continue to provide useful perspective and insights. But the unprecedented demands of the inflection point we are experiencing call for an expansion and update of a strategist’s repertoire. In a world where stability a brief pause, those who equip for uncertainty will not merely survive—they will shape the terrain of the next era.

The distinction between risk and uncertainty goes back to the economist Frank Knight who explained it in his book ‘Risk, Uncertainty and Profit’ published in 1921. The distinction was rejected by Milton Friedman and the Chicago school, but has recently been rehabilitated by John Kay and Mervin King in the book ‘Radical Uncertainty – Decision-making for an unknowable future’(2020).